Everything these six weeks taught me

“The Rule of the Loop: The more times you test and improve your design, the better your game will be.” – Jesse Schell (The Art of Game Design: A Book of Lenses)

I think I now have a deeper understanding of the above sentence by Jesse Schell pointing out the nature of design. I would like to share my thoughts on this quote and use the last six weeks of design loop to look back my personal work in the team and reflect on what these six weeks has taught me.

Team Formation

Starting with the team’s name, Maureen, Nicholas, Rachael, Joshua, and I got together to name our game design team. We had quite a few nice options, like Gaia Games Studio, GeoForce Studio, and Terra Learner Labs. Luckily, my proposed team name “ShowMeGeo Studio” was selected. It shows our identity, aligns with client expectations, and reflects our game’s goal—to introduce Geological majors. I am proud to be the creator of the team’s name.

Play More Games Before Designing One

Before we started designing the game, Dr. Oprean asked us to find, play, and share games related to geological majors. Through this exploration, I noticed many games were related to maps, possibly because maps are easier to design into games or simulations.

With the insights gained from playing games shared by other team members, I confirmed my assumption about the common use of maps in geological games. This led us to ponder: What other possibilities could we explore in geological game design? With this question in mind, we began researching our audience.

Understanding the audience is crucial for guiding our next steps in game development. By gaining a deeper insight into the interests, educational backgrounds, and gameplay preferences of our target players, we can tailor our game to better meet their needs and enhance their learning experience.

Researching Learner Persona

During the persona research phase, I drew upon my extensive experience as a secondary school science teacher to contribute to our team’s creation of learner personas. With 16 years of teaching in K-12 schools, I have observed many students choosing geography or related majors as they advance to college or graduate school. Recently, one of my former students, who is now attending the University of Nevada, secured a NASA research grant for his groundbreaking black hole research. Zhang, who was once just a curious young student in my science class in Beijing, China, is an example of the type of student who can significantly inform the development of our learner personas.

Given my background in geography and firsthand observations of secondary school students who pursue it as a major or research direction, I am well-equipped to assist my colleague Maureen in developing the learner persona, with a particular focus on those younger than college age. I am eager to contribute to the descriptions of our learner personas, particularly for high school and middle school students, leveraging real-world examples and experiences to ensure our game design effectively resonates with and educates this demographic.

Game Design

Starting from last semester, in Dr. Oprean’s course “Design Games for Learning”—the one before the current advanced course I am taking—I have been pondering the differences between games, movies, instructional design, and cooking. These thoughts frequently emerged in my mind, sparked by the many similarities between these disciplines. While writing a blog to review the past six weeks, these thoughts visited me again.

In my opinion, game design closely resembles movie design, instructional design, and even cooking. Why? Because all involve preparation: a game blueprint, screenwriting, a lesson plan, or a cooking procedure. The clients of the game, the viewers of the movie, the students in a class, and the tasters for a dish are the targets for these designs. All need interactive improvements if the creators wish to present the best to the end user.

You can find lovers of good food, elegant instructions, impressive movies, and playful games everywhere. Additionally, I think good games can also be attractive movies, informative instructions, and high-quality “spirit food,” especially in the case of story games like those ShowMeGeo Studio has been designing.

Schell, J. (2019). The Art of Game Design: A Book of Lenses, Third Edition (3rd edition). A K Peters/CRC Press. )

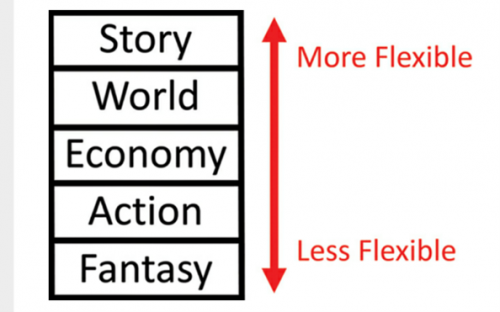

Jesse Schell used a figure (Schell, 2019) to illustrate the five important elements that comprise story games: Story, World, Economy, Action, and Fantasy. From this figure, I could confirm my imagination about the relationships between games, movies, instruction, and food once again. Because again, games, movies, teaching, and food can all contain the same five elements, and those elements can be improved upon by the designer.

For the importance of the story design in a game, Schell (2019) pointed out, “ When developing a game with a compelling story, it can be very tempting to start not by designing a game but by writing your story.” Now, let me focus on the story design.

Game Storming

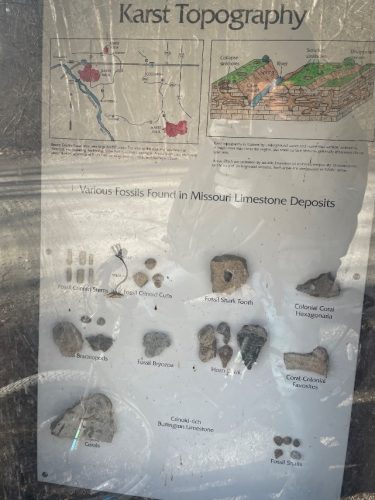

Where do good game ideas come from? Kultima concluded some points from the interviews that, “Good ideas were seen as inspiring for others to immediately build on top of them. It was seen as beneficial when a description gave enough information for other to imagine the idea, but enough space for them to develop it further. The bouncing of ideas would expose that quality of an idea.” (Kultima, n.d.) During a weekend brainstorming session inspired by Maureen, I developed a game idea while cycling on the MKT trail in Columbia, MO. This idea was influenced by geographic facts displayed on the trail (figure 3), leading to the creation of our game “CoMo Valley,” which incorporates different spaces and historical periods.

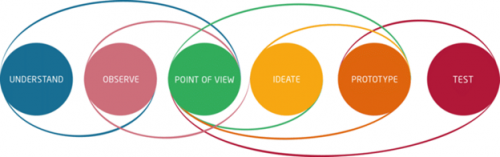

The Design Loop

When the five of us began sharing our specific ideas on a shared Google Doc, we quickly encountered a “chicken or egg” dynamic. This dynamic persisted in the following weeks as we developed the Storyboard, Objective Mapping, Assessment Plan, and the Concept Testing Report. We often debated which component should be introduced first: game mechanics, instructional objectives, assessment plans, or storyboard design? There is no definitive answer, as the ideal approach may vary from one game studio to another.

I confirmed this assumption during a guest lecture with Greg Marlow, who has extensive experience in both the game industry and academic settings focused on game design. The design process is inherently iterative—meaning the more times you test and refine your design, the better your game will become (Schell, 2019) . This also aligns with Dr. Oprean’s initial introduction to the course, where we embraced the concept of being in a continuous loop of development and improvement.

One key realization I had during our game development process is the importance of continually revisiting the problem description. I found myself rereading it numerous times to ensure that our design stayed aligned with the initial goals and objectives. This constant reference helped keep our project on the right track, ensuring that every element of the game design directly addressed the core issues we set out to solve. It served as a crucial checkpoint that guided our development decisions and helped maintain a clear focus throughout the iterative design process.

Problem Description

- There has been a steady decline in Geography majors over the years despite the real-world need for keeping the long-standing discipline alive. To better understand the problem, you can read a bit more on the decline here.

- Very few games and simulation solution exist to engage in the practice of Geography.

- Geography is a multi-faceted discipline with very diverse areas of practice, many of which are often confused with other discipline in Environmental Sciences and GeoScience.

- Geography in practice differs from what is taught in K-12 classrooms (K-12 classrooms focus on facts-based information where Geographers synthesize and draw meaning from human and environment interactions).

During this development phase, Dr. Soren Larsen shared his expectations for the game, emphasizing the importance of enhancing students’ abilities to analyze spatial patterns. The challenge was to design a game that not only helps novice learners understand the role of geographers but also trains students majoring in geography to analyze spatial patterns on thematic maps effectively.

To address this dual need, I suggested a multi-level design approach. This strategy allows us to cater to both novice and professional learners within the same game environment. By implementing different levels of complexity and challenge, we can ensure that our game is accessible yet sufficiently challenging to engage and educate players at various stages of their educational journey. This approach aims to provide a seamless learning curve that enhances the educational value of the game for all users.

Reflecting on My Process

As an experienced secondary teacher, I brought a lot of first-hand educational experience to our design process. Despite challenges in communication due to language barriers, I learned the importance of patience and persistence in game design.

New Content

The past six weeks have taught me the significant impact of patience in designing games, and the immense effort required to create games like “Stardew Valley” as an individual.

This process has been a valuable part of my learning and growth as a game designer, helping me to understand the intricate relationship between different creative processes and the importance of iterative design in game development.

References